I’ve been reading a book lately, “The Mind’s Eye” by Oliver Sacks, where the author, psychiatrist, and neuroscientist explores the effects of damage to the brain on vision. Initially I had thought the book would be about challenges for people who had lost their vision, either completely (blindness) or partially (legal blindness). As a counselor I was interested in learning more about how people adapt to such drastic life changes. However, as I read I discovered Sacks was exploring something altogether different, and I was intrigued with its implications for photography.

Early in the book Sacks meets, befriends, and studies a woman who has suffered a non-debilitating stroke in the visual area of the brain at the back of the head. Not only was the stroke not debilitating in the way we are accustomed to recognizing stroke victims, it actually went unnoticed to the victim-at least initially.

What was damaged in this woman was an area of the brain that processes visual stimuli-the area of the brain that makes sense of what we see. In effect, she began to have difficulty recognizing common objects for what they were. She could “see” them just fine; that is, there was nothing wrong with her eyes. It was just that her brain was not able to make sense of the visual input; the software got confused, as it were. This was most notable with sheet music (she was an accomplished pianist) as well as the written word. She was suddenly unable to read! (Oddly, the ability to write was unaffected-that skill is controlled by an altogether different area of the brain). Eventually this inability to recognize symbols and objects spread to simple, common, things like a banana or a bottle of mineral water.

Imagine seeing the shape and form of a banana but not being to recognize it as such.

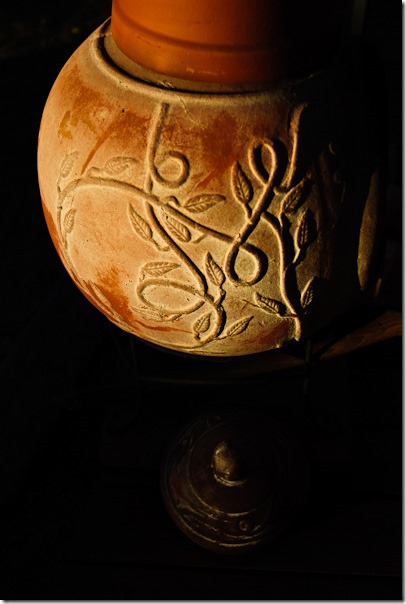

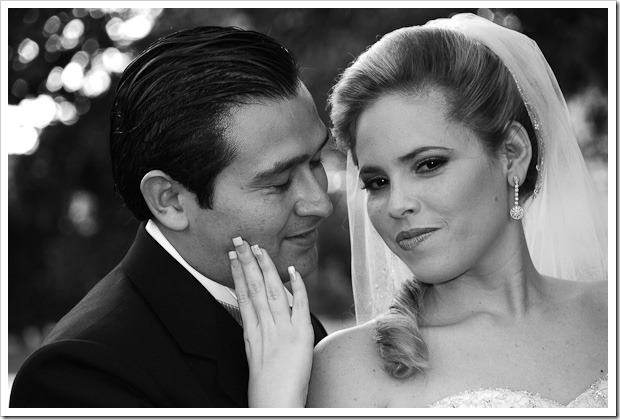

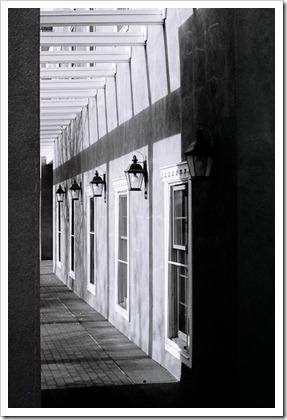

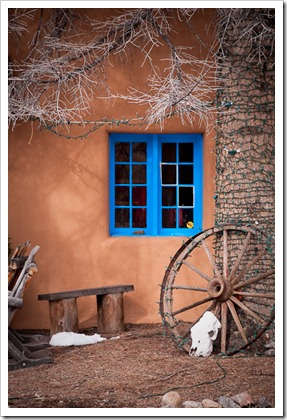

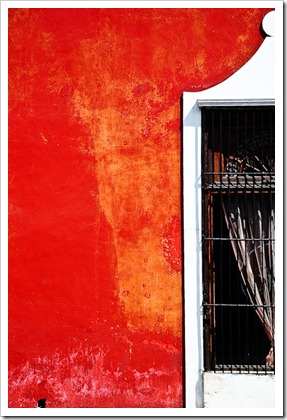

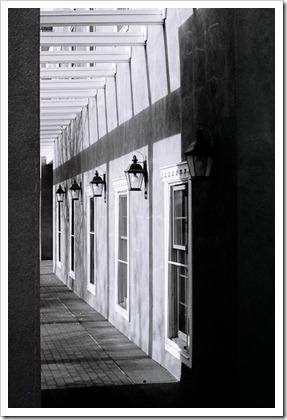

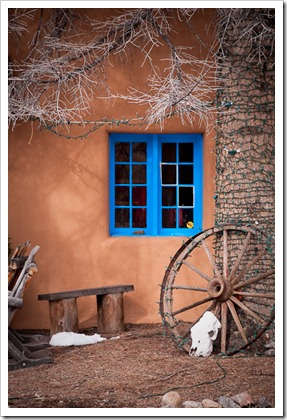

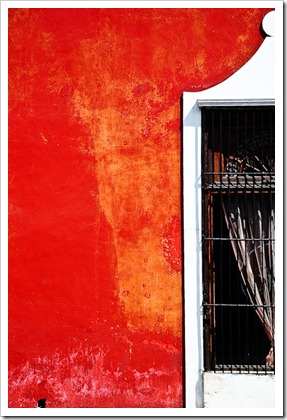

So this got me thinking; after all, this photography passion of mine (and yours, yes?) lies in a visual medium. What would our photography be like without the ability to recognize common objects as such? Some of my friends already play in this area of visual space; they are quite good at photographing space, shape, form, shadow, contrast. They can be drawn to it.

I find I have a hard time with this. Sure, I can photograph some lines and shadow, but they usually surround, are infused, and represent actual, recognizable things. Abstracts are much more difficult for me. I tend to be drawn to people, place, story, to humanity, to my human interaction with the world around. It’s really quite narcissistic when you think about it-as I see it, my world around me develops its meaning (at least for me) from my interaction with it. What would happen if I lost my ability to recognize shape and form as “things” or “people” and began instead to just see them as shape and form? And what meaning would I make from simple shape and form? How would that affect my photography. How would it affect yours?

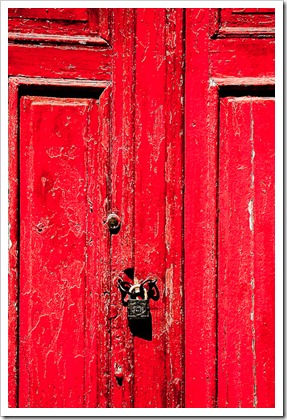

Many times I share with my family an image of something I like and the question that arises almost immediately is “what is it?” We want to make meaning of things and knowing what something is helps us to discover what that meaning is. It’s not a bad thing, but it can be limiting for an artist and photographer.

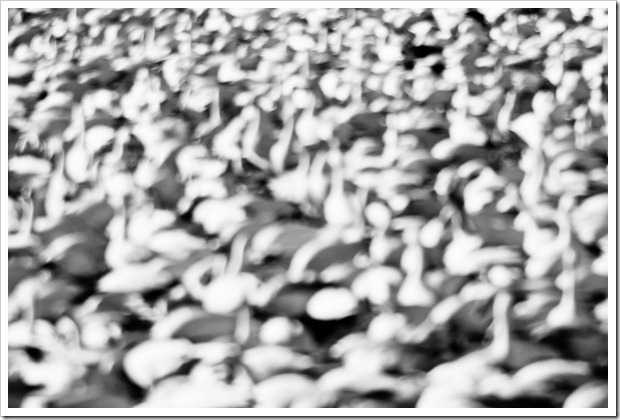

Lately, as I’ve been mulling these thoughts in my head, I’ve taken to playing with an old Pentax K1000 film camera. It is a fully manual camera and lots of fun. Having to shoot manual has suddenly freed me to play with focus. You see, autofocus and our generally conceived idea that pictures of things need to be sharp almost forces us to shoot things in sharp focus-bokeh not withstanding, but still there is an area of the image (the selective focus area) that is sharp. The K1000 has helped me to see that playing with focus can help remove the idea of the “thing/person” I am photographing and pay more attention to shape and form. It is a lot of fun and leading to a whole other way of seeing images in the world, and hopefully allowing me to stretch as a photographer.

The image above was intentionally shot out of focus. I don’t know if it works for others, but it works for me. Of course, I’m biased because I know what is in the image. The image at the top was an accident and caught me by surprise when I imported it into Lightroom. At first I was going to delete it but as I looked at it I started to see the possibilities and in the end I love it for being so representational of the melee of Snow Geese I was photographing that day. It is one of the images that gives the feel of the place for me.

What about you? Do you ascribe to the sense that images are best when sharp, focused, clear in visual representation and intent. Or do you like to play with representational shapes, lines, form, blur, out of focus?